Story:

Overcoming the mothership syndrome: the story of Irdeto

You probably know people whose mothers loom large - even in their adult lives. Their every move is slowed by the tugging of apron strings and the daunting consideration of what mother would think. In the business world, dominant mothership syndrome (an expression coined by Irdeto's CEO - see below) is also a lingering threat. It has a wide-ranging set of symptoms including tightly-controlled central resources, career tracks that favor HQ based staff, and a bias towards investing in new projects that reinforce the HQ power base.

How can you avoid these problems? Consider the case of Irdeto, a leader in securing and delivering premium content and digital assets. The Amsterdam HQ was replaced with a dual-core HQ split between Amsterdam and Beijing. Decision-making and traditional HQ functions were shared across the two locations. And to show his strong commitment to the change, the CEO moved himself and his family to Beijing soon after making the announcement. Over time a balanced organization - together with the accompanying senior management – is being created between the Beijing and Amsterdam locations.

Irdeto is not the first company to have created a dual-core or virtual headquarters. Sweden’s Ericsson tried moving some of its HQ functions to London a few years back, and Accenture operates a virtual HQ model with its top team split across several cities. But unlike these companies, Irdeto explicitly set up its organizational transformation as an on-going management experiment =with a clearly defined hypothesis about potential changes—that is, it engaged in true management innovation.

Irdeto is a trusted partner to many of the world’s leading content owners and distributors, device manufacturers and software companies, including Adobe, Skylink, Al Jazeera, Multichoice Africa and Televisión Cable Digital. Irdeto’s versatile technology platform ensures access to valuable digital assets and premium content through its content security, conditional access, business support systems and content and digital rights management product suites. By year-end 2006, it had revenues of US$129 million (€102 million) and employed 356 people in 11 offices worldwide. At that time, Irdeto’s core security products – conditional access (CA) and digital rights management (DRM) – enabled media operators to generate revenue by controlling when and how content was distributed to subscribers. The company historically targeted a niche segment of operators that valued robust security as well as Irdeto’s technological capabilities. Irdeto was an engineering driven, centrally controlled organization, valued by employees for the camaraderie and informal corporate culture in the head office in Amsterdam. Asia was Irdeto’s largest overseas market and its Asian operation, based in Beijing, included nearly a third of Irdeto’s employees.

The growth of Asia was driven in large part by Chinese government’s mass digitization initiative, which created a huge opportunity that Irdeto was quick to move in on. However, the same attractiveness had started to bring with it competition: local CA providers competed on price, used larger sales teams and leveraged stronger local relationships. International companies with larger resources were also beginning to make a move.

- Intensifying competition was creating a sense of worry that Irdeto’s European share would erode as a result of the entry of local competitors, who were able to achieve lower cost and also leverage superior connections with local government and regulatory bodies. International competitors were also looming on the horizon. Chinese vendors, especially China Digital, had been growing faster than predicted and the latest numbers showed that it had recently taken over the number one market position in China, with a 40% share. Irdeto continued to hold a leading position among foreign players; however, its overall share was down to 22%, although of a much bigger market, as the market continued to grow and new players were coming along.

- Lost deals in the latter half of 2006, which affected morale in the Beijing regional office. The China team felt that their urgent requests for specific requirements for the Chinese market were not taken seriously or dealt with urgently enough compared to the other demands on the organization. Centrally made decisions were felt to be contributing to the lost deals. An emerging feeling among some of the Chinese team members was that they felt like “second class citizens” within the organization

- Internal organizational challenges were exacerbating the situation. Strategic decisions were made at Amsterdam before being communicated to the regions, either by videoconferencing or in person during the visit of a senior manager. Irdeto’s regional offices were responsible for all local sales activity and operated as a “typical branch” in a global organization. Local managers were assigned specific authority levels for negotiation decisions, but Irdeto’s governance processes required that deviations from “normal” business practices be escalated to senior management at Amsterdam. For example, business discounts over a pre-defined threshold had to be approved by Amsterdam before they could actually be granted in the local market. While this “bid review” process was a carryover from Irdeto’s early days when sales were concentrated mostly in Europe, it now resulted in additional rounds of communication that hampered the company’s responsiveness and its ability to scale up effectively.

- Communications more broadly were a challenge. One manager, who had just been transferred to Beijing for a one-year work assignment, noted: “People would never think about my time when they scheduled a meeting. I always had to attend meetings in the evening but they never wanted to attend in the early morning to accommodate the time in Asia. And they didn’t even apologize if it was a holiday in China and I was working.”

In 2006, Graham Kill, the CEO, and his senior management team, began thinking about the exciting growth prospects for Irdeto, and potential barriers to this growth. At the top of his list was the firm’s dominant mothership syndrome, as he coined it – a syndrome that displayed some of the symptoms and problems described above. Kill [really prefer use from Graham than Kill – fits me and the company better]opted for a radical change: the Amsterdam HQ would be replaced with a dual-core HQ split between Amsterdam and Beijing. Decision-making and traditional HQ functions would be shared across the two locations.

Kill communicated the changes at an all-staff meeting at the company’s headquarters (HQ) in The Netherlands, which was broadcast live to the regions via the internet. This new office would build on the company’s existing activities (Asia-Pacific HQ, China sales and support, global engineering, marketing and product management) and create a significant Irdeto presence in the country.

This meant physically shifting members of the senior management team to ensure that the strategic decision makers were now physically present in Beijing. In August 2007, Kill and his family move to Beijing. By December 2007, Irdeto began to operate as a dual-headquarters model.

Kill was eager to measure the impact of the HQ shift on the organization, and specifically on the degree to which a dual-HQ approach would address the coordination and communication issues that were hampering Irdeto’s effectiveness. The company therefore launched a detailed questionnaire-based analysis of the patterns of awareness and interaction before the change, which was followed by bi-annual interviews and questionnaires to gather information as the changes are implemented.

Challenges:

Some people worried that key roles would be moved to Beijing, thus limiting the career prospects that had initially attracted them to Irdeto. Many of the company’s employees had started to work with Irdeto when it was small and solely based in The Netherlands. In most cases, they planned to build a career in Holland. The dual HQ announcement was a “reality check” that was really casting in stone the company’s earlier moves to the East.

The impact of the move was equally unsettling for some of Irdeto’s Chinese employees, many of whom had not anticipated the degree of change that would accompany Graham’s arrival. At Amsterdam, Irdeto had just begun implementing an open-plan office and flexible desk policy for all employees as a pilot for its new building: Employees switched working space every day according to their requirements or the projects they might be working on. Senior managers sat together with employees and the only closed-door offices were general meeting rooms. This approach contrasted with the Beijing office, where local senior managers still had closed, individual workspaces. Employees in Beijing were very accustomed and comfortable with this traditional division of space. But Kill decided to pilot the open and flexible-space approach in China – both to convey Irdeto’s global philosophy and at a more practical level, to accommodate the fact that more space was needed in Beijing to implement the dual HQ approach. Many Chinese employees were surprised when Kill sat among them.

Solutions:

Graham instigated several initiatives to promote a change in mindset and reinforce the “transnational” management model. He encouraged the Beijing team to alternate meeting times with Amsterdam so that half of the meetings occurred during Beijing working hours, while the other half accommodated a European time schedule. He suggested rotating the role of chair during meetings, so that all managers got an opportunity to lead. All meetings had to be conducted in English, and they had to examine issues that affected Irdeto beyond China.

Graham also firmly believed in leading by example. Such a change in working approach would only work if there were no exceptions, including the CEO. For about a year after his move, there were still middle managers installed in their offices while Graham sat in open space.

Many employees at Amsterdam embraced the potential of the dual HQ for international exposure and potential work assignments abroad. They expressed optimism about Irdeto’s growth and their association with an innovative global company. Many of the strongest supporters of the dual HQ were self-named “global junkies” who had been drawn to Irdeto by the allure of international opportunities.

In the Beijing office, the dual HQ announcement generated “positive surprise and a lot of excitement.” Many employees perceived the move as one that would heighten their role within the organization. Finally, they would be able to participate in strategic decision making and present opinions instead of just implementing instructions. Employees were excited to be at the heart of the company and to work in a global office.

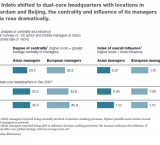

The new arrangements also led to measurable changes in internal attitudes and behavior. Irdeto’s survey of managers before and at two periods of time after headquarters shift (2008 and 2009), showed a dramatic change in the degree to which managers based in Asia found themselves centrally involved in and able to influence decision-making processes. By 2008, the centrality of Asian (not just Chinese) managers rose more than 20 percent, and their level of influence increased nearly 30 percent. By the time of the 2009 survey, in fact, the influence scores for Asian managers actually exceeded those for Europeans (see attached chart). The quality and quantity of communication between the Asian and European parts of the company also improved significantly .

Sales in Asia-Pacific were growing and the local presence of senior leaders was enabling greater responsiveness and a more informed view of markets outside Europe.

The mothership syndrome can have damaging consequences. Sales leads in unfamiliar parts of the world are not given attention because of a lack of awareness. Promising employees in branch offices leave the firm because of a perceived lack of career openings. Money gets invested in projects that reinforce activities and positions close to home. Taken as a whole, these can put you at a competitive disadvantage.

Dual HQ strategy should be more than a symbolic move. In the case of Irdeto, it brought a necessary change in Irdeto’s center of gravity. Moving forward, this could establish Irdeto as a more flexible organization aligned with the changing nature of its markets.

Set up organizational change as an on-going study with a clearly defined hypothesis about potential changes. You can’t run a laboratory experiment in a real-life setting, but with careful planning you can control many extraneous factors, and you can directly assess the consequences of your actions.

Here are some quick responses to the questions posed by readers:

Peter Forth: yes, its interesting to ask whether this story would be such a "big deal" for the Gen Yers in the workplace, who have grown up in a world of virtual collaboration. There is no question that virtual head offices are becoming more common - many professional services companies like Accenture and McKinsey have already moved to such a model - and my guess is that there is a lot more of this to come.

Ellen Webber (and others): I am not wedded to the "mothership" metaphor, as you rightly point out that it has some inappropriate connotations. But the dependency syndrome, or the learned helplessness, of subsidiary units when faced with an overbearing HQ, is all too real in organisations large and small.

which brings me to your first point - I think its interesting to note that Graham Kill would probably have failed to make this enlightened move if he had been democratic about it, because there would undoubtedly have been resistance in some quarters. So decisive, top-down leadership is sometimes necessary to create lasting change that helps people in the lower levels of the hierarchy.

- Log in to post comments

An interesting look at diversity here - with a keen attempt to work with and value diversity. Thanks! That target requires a new model - new metaphors - and new tactics, as this post points out with such skill.

There were two questions I had when reading:

1).The CEO - Kill - appeared to deliver the new "solutions" - and I wonder what effect these might have at sustainable levels had he negotiated them with all people affected by the challenges? Would people have spoken and felt heard on issues that worked against them. Would different solutions - such as meeting times - been different?

2). Did all agree with the metaphor used to show stagnation, and control? Mothership syndrome, appears to omit any caring, nurturing or talented roles associated with mothering – and uses highly negative view of women who happen to mother. It’s perhaps less problematic if f there is a healthy gender mix of 50 – 50 or so. Perhaps this metaphor would be less serious, if women are highly valued, and their proclivities developed. But if intelligent women are fewer in the organization, or if they are excluded from leadership – that metaphor could be working against the very diversity efforts named in your Moonshot.

Could you elaborate a bit more on these two issues – with thanks for sharing this international reach!

- Log in to post comments

My mother is a sculptor. She raised five children alone as her husband (my father) died at a very young age. He was 36, my mother was 34, I was 6.

Before and since she worked like hell. To provide for us and for herself. To carve herself in stone, her loneliness, her heart, her feelings. And to provide for us, her children.

I resent stereotyping 'mothers'. Mothers can be everything.

Best, Mireille

- Log in to post comments

I'm interested to see how the next generation of workers, brought up on social networking, will solve such problems. That said, and as per your example, I don't think we can wait that long.

For the younger generation, collaboration online is second nature where physical location is much less of an influence on sharing information. Bringing these technologies and behaviours that into the workplace to help solve such issues has to be harnessed but in my experience, to make things work we'll need to do 2 things well:

1) Find a way of making this collaboration part of day to day life through technology, process and planning

2) Mandating and/or rewarding the right behaviours e.g. exec level sponsorhip and individual performance management where wider collabroation is noted

That is until we reach a tipping point where those in the right roles find the concept of a mothership so alien that they sort it out for us.

- Log in to post comments

Interesting idea, and I see the 'mothership syndrome' relevant to any multi-location multi-divisional organization, because today's customer social network driven marketplace, it is difficult to innovate without developing and leveraging an open network inside the organization: And, the mothership syndrome is a great enemy of such open network, as it excludes people at the front line and deprives them, more often than not, from effective participation in 'imagining the organization' [they may have a say in decision making].

- Log in to post comments

You need to register in order to submit a comment.